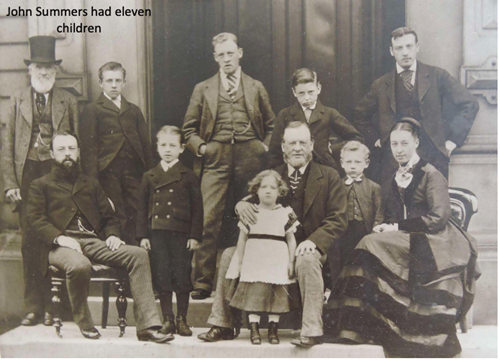

History of Shotton Point

The John Summer Clock Tower building opened in 1907 and was the headquarters of Shotton Steelworks, before closing in 2009 and falling into serious disrepair after being sold by the company. Wilsons Auctions have now taken on the restoration project, with a view to securing the future of the historic and Grade II listed site.

Wilsons Auctions bought the site in 2020 in a decrepit state and is undergoing a restoration project to bring life back to the historic buildings and estate.

There was a major concern that the buildings would be sold to a developer and the heritage of the estate would be lost, however as a local employer, Wilsons Auctions has committed to a renovation project that will return the estate to something of its former glory. This will allow the estate to be enjoyed by future generations, as there are plans to create a community hub, heritage centre, café, library, and reflection areas.

TIMELINE

With no room at Stalybridge for further expansion, the Summers brothers start their search for a site for a second works. Henry made his way to a boatyard at Connah’s Quay and asked for a boatman to take him up the River Dee. Bill Butler was given the job and he rowed Henry upriver in the direction of Chester. When they returned to the boatyard, Henry gave young Butler half a crown for his services

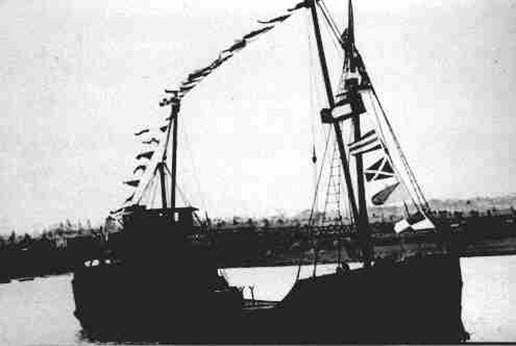

The Summers’ main requirements were for a nearby source of water and for the site to be within easy reach of Liverpool. The River Dee and the recently constructed railway adjacent to the land made Shotton ideal. The reclaimed marshland of the Dee was cheap and in 1895, Summers’ purchased 40 acres at the reputed price of 2s 6d per acre, a total of £5! A further optional 50 acres was negotiated and £610 was paid for railway sidings connecting to the M,S & L Railway. In December of that year, as noted in the minutes of a meeting of the M, S & L Railway Company, John Summers and Sons had acquired part of the golf links of the Chester Golf Club. A platform built for the club had to be moved, for £190. (The photograph below is of the Hawarden Bridge)

By 1896, 25 workmen’s cottages were being built on the opposite side of the river in Shotton. As the works expanded, men travelled daily by train from Wrexham, Rhyl, and Prestatyn. A walk along Chester Road West in Shotton will reveal the prosperity brought to the town by the Summers Steelworks in its first few years. Starting from near the Wepre Brook bridge, on the north side of the coast road, a row of terraced houses, extending right down to the Station Hotel was built in 1896. Each block was named and most of the name-stones can still be read on their walls. Amongst them are: "West View," "Hillside," "Filbert Terrace," "Cambrian View," "Avelon Cottage" and "Shotton Villa." "Claremont Villa" on the corner of Chester Close, and until recently a doctor's surgery, was also built in 1896. In 1908, on completion of new offices, the company transferred its headquarters to Shotton.

This elegant symmetrical building of polished red brick and terra-cotta is said to resemble the Midland Hotel in Manchester. It was designed by Henry’s friend, James France, and is of Edwardian style. It consists of 5 storeys, and its imposing, castellated central clock tower still overlooks Shotton today, contrasting with the high-tech factories that surround it. These villages began as a planned community for workers of the nearby steel works in Shotton, in accordance with company policy to give their workers decent housing. These villages were originally intended to be called "Sealand Garden Suburb" and were planned to be four times bigger, but construction was halted by the advent of the First World War. (Below is a photograph of Shotton Point).

This elegant symmetrical building of polished red brick and terra-cotta is said to resemble the Midland Hotel in Manchester. It was designed by Henry’s friend, James France, and is of Edwardian style. It consists of 5 storeys, and its imposing, castellated central clock tower still overlooks Shotton today, contrasting with the high-tech factories that surround it. These villages began as a planned community for workers of the nearby steel works in Shotton, in accordance with company policy to give their workers decent housing. These villages were originally intended to be called "Sealand Garden Suburb" and were planned to be four times bigger, but construction was halted by the advent of the First World War. (Below is a photograph of Shotton Point).

While the works grew the hamlets of Shotton and Connah’s Quay had an influx of workers and their families. The works and the community grew together. In 1902 a group of managers in the works formed Summers Permanent Benefit Building Society to fund house purchase. James Summers was president and mortgages were repaid directly from workers’ wages. By 1909 John Summers and Sons was the largest manufacturer of galvanised steel in the country and by 1910 the workforce had grown to 3,000 the policy of building houses for workers financed through the company building society helped attract men to the area. (The photograph below is of the Steel Works Crew).

1911 - 1972

1911 - 1972

“On 26 August 1918 at Bazentin-le-Grand, France, when the advance of the adjacent battalion was held up by enemy machine-guns, Lance-Corporal Weale was ordered to deal with hostile posts. When Lewis gun failed him, on his initiative, he rushed to the nearest post and killed the crew, then went for the others, the crews of which fled on his approach. His dashing action cleared the way for the advance, inspired his comrades, and resulted in the capture of all the machine guns.” Harry survived the war, returned to the steelworks, married Susannah Harrison, and moved from Shotton to Rhyl where he died in 1959 at the age of 62. (The photograph below is of Henry Weale)

Throughout the war, the works ran at full capacity. One of the Hawarden Bridge Works' most famous products was made in this period. It was corrugated sheeting that was curved and punched to make self assembly kits for the famous Anderson Shelter, which saved many lives during the Blitz. Fifty thousand were produced every week, but a shortage of zinc, used to galvanize the sheets, meant that the Morrison Shelters, designed for indoor use, superseded the Anderson Shelters. (Photograph of the Anderson Shelter Kits waiting in Sidings at Hawarden Bridge Station).

The works were well-known to the German Luftwaffe, as shown by a map dated September 1941 and retrieved from an enemy plane brought down nearby. Low-flying raids were hazardous because of the low-lying Clwydian range of hills and decoy lights on high ground and the Dee marshes made bombing difficult for a plant crucial to the country’s war effort.

In the event, not a single shell or bomb fell on the works during the war, and on 22nd May 1945 Richard Summers spelled out the extent of the contribution made in defense of the country. During six years of continuous high-pressure operation, the works had produced 3.3 million tons of steel ingots, and 2.2 million tonnes of sheets, sufficient to make over 60 million steel ammunition boxes, over 40 million jerry cans, and 16 million oil drums.

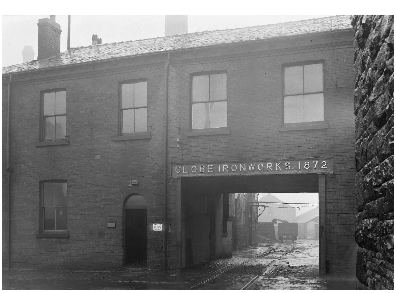

In 1969 the Globe Ironworks closed down in Stalybridge, and following many years of speculation, the party finally ended in Shotton three years later. In 1972 B.S.C. announced a 10-year plan that would culminate in the loss of about 7,000 steel-making jobs. All 13 unions fought the closure but were unsuccessful. In 1973 the government announced it would phase out iron and steel making at Shotton. This ended eighty years of Summers’ family history but not Peter’s. He was given the responsibility to assist some of the 6,500 people who would lose their jobs as a result. Thus started the second and most rewarding part of his career.

The last cast of steel produced passed by virtually unnoticed, and without ceremony, for the works was on strike at the time. The end of steel-making at the site was devastating to Shotton and the Deeside area, which relied heavily on the works as the main employer in the area. Shotton now takes its unenviable place in history as the community that suffered the greatest mass loss of job opportunities in living memory. The closure of the cold strip mill and an electro-galvanising line in 2001 saw the workforce reduced further. Shotton Steelworks now employs a mere 700 in what has become a state-of-the-art steel coating.

The development of a new industrial park for Deeside was announced in 1976 with Peter J. Summers, great-grandson of John Summers, appointed Industry Co-ordinator, Shotton, with BSC Industry Limited, the job-creating subsidiary of BSC. (The photograph below is of Peter John Summers)

Since the Shotton steelworks closed in 1980 many of the men made redundant have never worked again, according to those who lost their jobs. Former steelworkers say that much of the industry brought into the area and sited at Deeside Industrial Park has consistently refused to employ anyone over 40.

Defending the decision to make 30,000 miners redundant, the Prime Minister said that he had recently visited the site of the old steelworks where 10,000 jobs had been 'lost in a single day'. He added: 'There is now a modern industrial estate there providing secure, permanent employment for the people who once worked in those Shotton steelworks.'

In 1980 John Summers Building Society merged with the Cheshire Building Society to protect the interests of its 9,600 mortgagors and investors following BSC’s announcement to end iron and steelmaking. The Summers Society had assets of £7.5 million and reserves of £373,000 at the time.

Wilsons Auctions bought the Shotton original historic Administrative Office and associated buildings in February 2020 in a decrepit and derelict state. There followed some initiatives by local community groups to endeavor to save the site, however, they didn’t possess the infrastructure, funding or general know how to take on the task. (The photographs below are of the Summers Headquarters Building at the beginning of the renovation)

By 2023 it became apparent that the buildings, in particular the Clock Tower would not survive another winter; the roofs were collapsing and water ingress was steadily destroying the iconic historic features, so it was decided that Wilsons would take on the renovation and site works, rather than lose the iconic site to the elements. The multi-million pound investment programme will see the site restored to its former glory and will feature community gardens and a museum area in the Clock Tower. Visitors will be able to enjoy a historic tour and get their picture taken at the iconic main stairway which was made by the same manufacturers of the stairway in HMS Titanic.

View the FULL Shotton Point Before & After Presentation